The New York Times reported on these diaries, noting that one participant, Dennis Cheatham, reported having no room to log the time his family spent watching Netflix, “I just kind of shoved it in there and wrote Netflix wherever I could.”

To be fair, paper diaries aren’t the only way Nielsen generates TV ratings. They also use Nielsen meters, which are attached to participant’s cable boxes.

Nielsen counts the number of people in the prized 18-49 demo who watch TV ads live, up three days after air (C3), and up to seven days after air (C7). The viewers for C3 and C7 aren’t valued nearly as much as live viewers but are included to capture DVR viewings.

Yet even with meters, it’s difficult to know if a viewer is truly engaged with what they’re watching. For example, Nielsen may know what channel a cable box is tuned to, but they can’t determine if the viewer’s television is actually on.

Even worse, Poynter has reported research that shows Nielsen still doesn’t get enough data points to have a representative sample, even as they’ve increased their sample size to 40,000 households — and the data they do get has in increasingly high error rate. Nielsen has also had to reveal to their biggest customers, the big TV networks, that they had been giving them inaccurate ratings for a 7 month period in 2014, raising questions as to how long these inaccuracies have plagued the company.

It’s easy to see why the networks, who pay $100 million annually for Nielsen’s services, are frustrated not only with declining ratings across the board, but with Nielsen’s failure to keep up with the changing media landscape. One begins to wonder how a 94-year-old legacy could possibly be up to the task of measuring viewer engagement in an increasingly fractured media landscape.

In Neilsen’s Wake Comes Metrics For All

With the rise of Over-The-Top (OTP) streaming video, like Netflix and Hulu, Nielsen has been trying to play catch-up with a data collection strategy fitted for the 1950s, as 30% of Nielsen’s data is still collected from the aforementioned diary entries.

Because they largely haven’t been up to the task, media companies have been left to their own devices to develop the means to measure their audiences. As a result, we have a mess of metrics and no way to measure apples to apples. The colossus in video streaming, Netflix, doesn’t even publicly release their data to advertisers or content creators, creating something of a “black box” informational advantage.

Social media platforms have attempted to measure their streaming audiences, with mixed results. Facebook counts video views starting at three seconds. They’ve run into their own issues, admitting they overestimated the average viewing time for video views for two years. Snapchat counts views as soon as a video starts, and YouTube does so at around 30 seconds.

YouTube has also been dealing with an “Adpocalypse,” with major advertisers like Coca-Cola, AT&T, and General Motors pulling ads after finding they were being played before offensive videos containing hate speech. In response, YouTube instituted a broad demonetization policy for videos containing advertiser unfriendly content, causing an uproar among legitimate creators, some of whom reported losing half of their incomes in the aftermath.

Twitter’s recent foray into live NFL broadcasts wasn’t the boon in engagement they hoped it would be. They reported a Thursday night game had an average minute audience of 327,000 viewers, while on CBS and NFL Network it was 17.5 million.

With all these media giants developing their own proprietary metrics as an alternative to Nielsen ratings, the future of TV audience measurement is more uncertain than it’s ever been, leaving advertisers to wonder what they’re really paying for.

For decades, Nielsen was able to present an apples to apples comparison of audiences across television that both advertisers and networks swore by. Because Nielsen hasn’t been able to catch up with the demands of audience measurement in the 21st century, the industry won’t have a way to compare audiences—it will inevitably being comparing apples to oranges, with each entity creating their own metrics for their advertisers.

Remember, Nielsen is a 94-year-old company that has had a virtual monopoly in an industry largely unchanged since the 1950s. They built their model in an era where the family gathered around the TV set every night to watch one of the three big networks. That era is completely irrelevant today.

With people able to watch their favorite programs on streaming platforms on their phones or laptops, TV ratings across the board have been shrinking, even typically dependable live sports programming. In turn, networks are facing shrinking ad buys because Nielsen is reporting smaller ratings as the media landscape fractures. Yet it stands to reason people are watching more video content than ever, the problem remains Nielsen isn’t able to measure viewers effectively.

Not that they haven’t tried. For example, Niesen has starting to track different devices like PCs, but they use a representative panel that is too small to measure today’s fragmented audiences. They’ve also developed software to measure mobile and tablet devices, but industry executives complain that it’s filled with bugs.

As another example, Nielsen has attempted to break Netflix’s analytics black box, but the results have been less than stellar, to put it nicely. Their method monitors audio when participants are watching Netflix via their TV’s set-top box, which is based on a similar method used in Nielsen’s radio days. The first issue with this methodology is that it is opt-in, which pretty much guarantees a selection bias in their sample. Second, their method doesn’t measure the viewing habits of any Netflix subscribers who watch on their phones or tablets, which represents two-thirds of Netflix’s customers!

All the while, Nielsen is faced with a more nuanced task—keeping their customers, namely TV networks—happy. The TV industry would be thrilled if Nielsen came up with an efficacious way to measure today’s media consumer, but if that means those numbers aren’t going to increase their advertising sales, they might as well forget it. By having to serve two masters, Nielsen finds itself in an unresolvable conflict.

A New Paradigm For Media in the 21st Century

To change a broken system, you have to reform it from within or create a new one so great that the old players can’t ignore it. AlphaNetworks has chosen the latter.

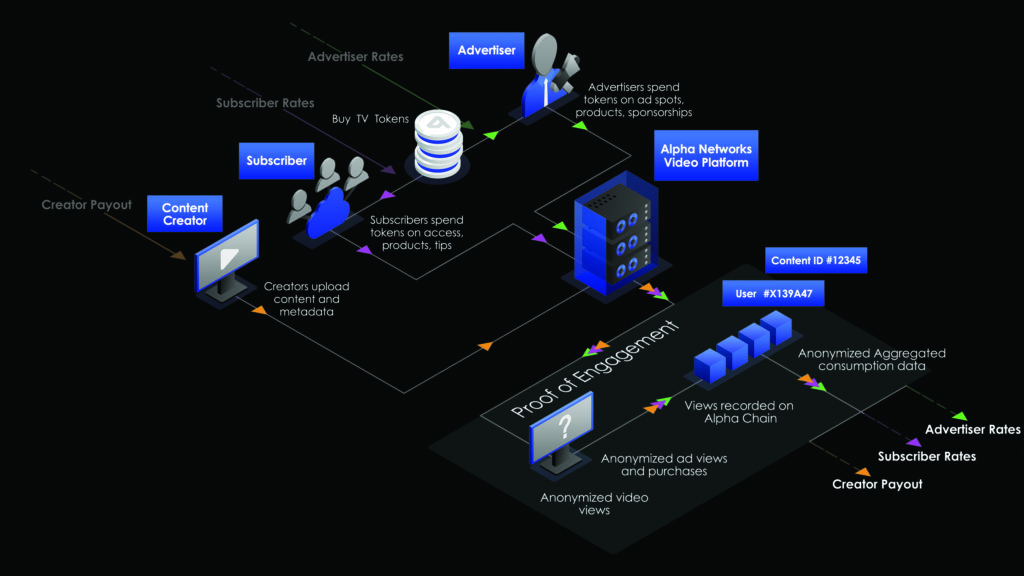

AlphaNetworks solves TV’s audience measurement problem by using the blockchain to irreversibly record all engagements between users and content.

We’ve developed a “Proof of Engagement” (PoE) algorithm, that will create the foundation for the most efficient and transparent payment and reporting system the media business has seen to date.

Here’s how it works.

Proof of Engagement is a data point that establishes that an interaction between a user and some video content has taken place.

These interactions can be any of the following:

- Viewing a video for N seconds

- Clicking on an in-video advertisement

- Finishing an in-video activity, such as a questionnaire

Engagement is established on AlphaNetworks servers with proof of the engagement being anchored on the blockchain. This means every act of consumption is verifiably recorded, with the resulting actionable data transparently supplied to participating networks, creators, and advertisers.

Of course, all viewer data is fully anonymized and analytics are completely segregated from viewers’ personal info.

This replaces the old and inefficient model used by legacy companies like Nielsen to measure audiences, and allows for a new economic model for creators, advertisers, and networks to form.

Rights holders will receive direct payouts based on consumption using PoE, as well as transparent access to a robust dashboard of analytics.

Users can spend directly on the platform on a variety of goods and services directly from the user interface.

And advertisers will get invaluable insights from Watson AI’s predictive analytics, automatic visualizations and customizable dashboards.

AlphaNetworks’ anonymized Proof of Engagement (PoE) is a highly accurate, transparent method for measuring engagement within the Alpha Networks ecosystem. It provides a true apples to apples metric for media consumption in the 21st century. The PoE approach ensures timely transactions to all participants—including content creators, users and advertisers — throughout the AlphaNetworks ecosystem.